What Is Rising Damp?

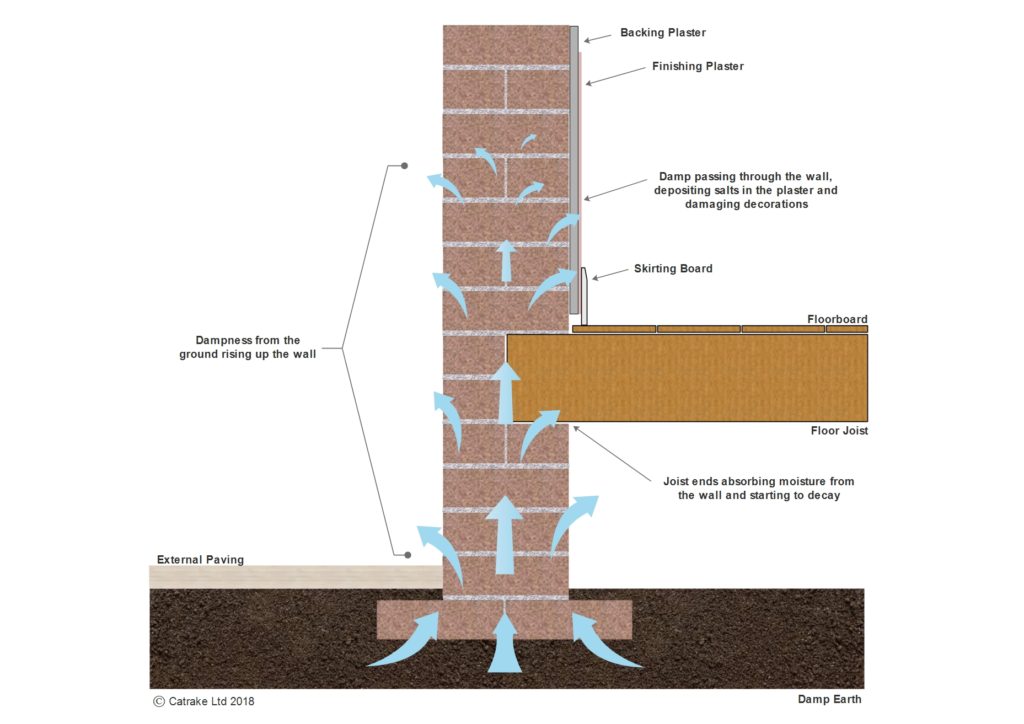

Most building materials which are used for walls are porous, that is, they will absorb water if they are in contact with it. This is because the materials are not solid, but contain many very small holes called pores and capillaries into which water can pass. As water spreads through porous materials it draws more water along behind it – even against the force of gravity – in much the same way that a kitchen towel will absorb a small spill of water if just one edge of it is dipped into the water.

This mechanism means that a wall in contact with the wet ground will absorb water and the water will also pass up the walls – this is rising damp. Rising dampness is the result of capillarity, this being the process in which water rises up the very fine tubes formed by the pores.

As the water passes up the wall, it evaporates away from the surface at a rate mainly depending on the temperature and type of wall covering. Eventually, the amount of water passing into the wall is balanced by the amount which can evaporate and the water does not reach any higher up the wall. This may result in a tide mark being seen across the wall – below it, the wall is constantly damp, but above it is relatively dry. The height of the tide mark depends on the dampness of the ground and how quickly water can evaporate from the wall. If the wall is coated with a water-resistant covering, such as tiles, gloss paint or vinyl paper, the damp may reach much higher before it can evaporate. Rising damp rarely rises above a height of 1 metre above the external ground level and/or the internal solid floor level.

Often the rising water will carry salts into the wall from the ground. These can react with plaster or brickwork and a deposit of crumbly white crystals may be seen on the surface. They can be brushed off and may build up again, and affected plaster will eventually perish, becoming soft and falling off.

Rising damp can be most costly when timber floors are affected. In older houses, floor joists are often seated directly into walls, with little or no protection from the dampness. Joists are usually supported directly on to the physical damp proof course in more modern building constructions. Where rising dampness exists, masonry, on which the timber joists are supported, becomes wet. Eventually, damp wood will become infected with wood-decaying fungi such as wet rot or dry rot, and may also become attacked by wood-boring beetles. These cause a complete breakdown of the structure of the wood and the floor may eventually collapse. This can occur over a short period, or take many years, depending on the degree and speed of development of the dampness and the resultant fungal or insect attack.

Joists can be protected by chemical treatments and wrapping the ends in a damp-proof membrane before inserting them into a damp wall. (Even a wall which has been damp-proofed will still contain some residual moisture and it is important that new replacement timbers are also treated in this way.) Better than chemical treatments, is to ensure joist ends remain dry – but this is not always possible.

Treating Rising Damp - Damp-Proof Courses

Old buildings were constructed with little or no protection from rising damp, but in more recent times rising damp has been prevented by inserting a layer of water-proof material into the wall as it was built. This was often slate, poured bitumen or bituminous felt, but nowadays is most likely to be a layer of PVC. Although some of these have a long life, it is possible for these substances to perish and allow water through. This is not the case in modern PVC damp-proof courses.

Luckily, it is possible to damp-proof most buildings without dismantling them. The main methods used today are chemical injection, mortar injection, electro-osmosis and sometimes the insertion of physical damp-proof courses or other types such as evaporative clay pots set into walls. (Insertion of physical damp-proof courses and the clay pot method are not discussed further here).

Chemical injection is the most suitable and cost-effective method for solid brick and cavity brick walls. The other methods are necessary for thicker stone and rubble-filled walls. They may also be suitable for breeze block walls, which are difficult to treat because of their open structure and brittle nature when drilled.

Chemical Injection

This method involves drilling holes into the wall at approximately 100 mm intervals and injecting a solvent or water-based chemical into the wall under pressure until the wall material is soaked with the chemical. The chemical layer then controls water rising past it. There is also a newer system involving the injection of a damp-proofing ‘cream’ into holes. Here the cream is injected into the wall from a caulking gun via a long nozzle. Solvent-based materials have largely been replaced by water-based fluids (primarily on safety grounds – solvent damp proofing chemicals are flammable).

With this type of water-based or cream chemical the injection is carried out into the mortar layer between the bricks (solvent-based chemicals may be injected into the bricks themselves). This is usually at a perpendicular joint to give approximately 2 injection holes per standard brick width. This is a spacing of about 110 mm. The holes on the outside of the property are filled, but those in internal walls are usually left open.

If possible external walls are injected from both sides to ensure complete penetration of the chemical, but where access makes this impossible the wall is double drilled from one side, with each hole being drilled and injected, and then drilled deeper and re-injected to ensure the chemical reaches all parts of the wall. This is sometimes called double drilling / double injecting the wall. An advantage of the cream system is that it is designed to treat thicker brick walls and can be inserted from one side only via deep drilled holes.

Where fluids are used, it is important that the drilled surfaces of the wall are visible when injecting – so any plaster or render must first be removed, otherwise, the chemical may be injected down between the wall and its coating instead of into the wall itself. Seeing the injection point also helps to determine the optimal saturation of the wall area by the injected chemical. Plasters and renders should be permanently removed in the area of the damp proof course so that it is not bridged.

Cream-type damp proof course injection has become the standard for the industry, because of the reliability, ease, and quickness of installation. Now we use mostly these.

The height of the new damp-proof course in relation to external ground levels and any floor timbers is also very important to ensure that floors are protected from dampness – see the section Bridging Of Damp-Proof Courses below. Further information about this can be found from British Standard BS6576:2005 (not reproduced in these web pages).

Mortar Injection

This is a similar technique to cream chemical injection, suitable for treating thick stone walls where rising damp is largely carried by the mortar beds and rubble filling. Larger 20 mm holes are drilled at about 100 mm intervals and the damp-proofing agent is a pore-blocking chemical contained in a fine sand/cement mortar.

The damp-proofing agent is carried into the porous mortar beds and rubble by the rising damp, where it crystallises to form an impermeable barrier to control subsequent water rise.

The drilling is more time-consuming and the materials more expensive than the liquid or cream chemical injection, but the results are much more satisfactory for these types of stone walls. Mortar injection can also be used in conventional solid 225 mm or cavity 275 mm brick constructed walls.

Plastering

Even when a new damp-proof course has been installed and the rising dampness controlled, the wall will still contain water from the previous dampness, together with salts carried up from the ground. These will continue to attack plaster and decorations. Gypsum based plasters will be changed by the action of the salts so that they actually attract water from the air, and may never dry out. It is therefore important that the old perished plaster is removed and replaced with a special plaster system which resists attack by the salts. This is sometimes referred to as renovating plaster or chemical rendering and can be purchased as a special plaster system or mixed according to a particular specification. More recently plaster systems have been developed that comprise of physical membranes and drywall linings.

The replastering, therefore, forms an integral part of the damp-proofing work and must be carried out properly if the new damp-proofing system is to function effectively.

Bridging of Damp Proof Courses

The damp-proof course installed in a wall controls water from moving up the wall, but this is obviously useless if water can by-pass around it. When this happens this is referred to as bridging. The most common form of bridging is when the ground level outside a solid wall is higher than the installed damp-proof course. Other forms of bridging include internal plastering and external wall renders extending down over the damp-proof course line.

If soil or paths are allowed to touch the wall above the level of the damp-proof course, groundwater will be in contact with the wall and rising damp can occur. Exposed timbers bearing onto the wall may also be at risk from dampness and therefore may rot. Even if the ground level is below the damp-proof course bridging can occur in a solid wall when rainwater hits the ground and splashes on to the wall above the damp-proof course.

For this reason, the ground level should be at least 150 mm below the damp-proof course (which should be below the level of any floor timbers, if at all possible). If a path or driveway is too high, the situation can be improved by digging out a channel along the wall (about 300 mm wide) and lining it with gravel, to act as a soak-away.

Impossible to see without an endoscopic view of the cavity, and even then difficult to evaluate its extent, is cavity blockage at low level due to debris. This can build up in the cavity as mortar erodes inside the cavity and drops downwards. Alternatively, bad house building can leave the cavity full of mortar droppings from when the bricks were laid.

The solution is to clear the cavities, raking out material that would otherwise lead to bridging across the cavity.

This is usually carried out by the removal of bricks on a line below the line of the damp proof course. Sometimes in one location access is improved by removing up to three bricks on two levels.

The idea is to rake out the debris and clear the cavity above the line of the damp proof course, so that bridging, and therefore movement of moisture from the outer to inner walls, does not occur.

Having removed bricks, advantage should be taken to improve sub-timber floor ventilation, if needed. Any wall insulation that has been removed must be replaced.

Tanking & Structural Waterproofing

Sometimes it is impossible to prevent walls being in contact with high ground levels; an underground cellar or a house built into the side of a hill, for example. Most common is the positioning of local authority pavements in relation to internal floors. These are ground levels that can not be reduced and so some tanking or structural waterproofing must be used.

In these cases, the only way to completely damp-proof the walls is to install a damp-proof course above ground level and to apply tanking or structural waterproofing to the inside of the walls below ground level. Sometimes this water-proofing layer can be applied to the outside of the structure, as part of the construction, or by digging out ground levels, installing the tanking/structural waterproofing layer, then replacing the ground levels. Tanking is used as a generic name for structural water-proofing and takes various forms. These treatments effectively create a barrier to water, much like the inside of a swimming pool.

It should be noted that any timbers bearing on to walls that need to be tanked, because of high external ground levels, will be highly at risk of attack from fungi and wood boring beetles. This could result in the failure of the timbers.